The New Yorker: Death of a prosecutor

Alberto Nisman accused Iran and Argentina of colluding to bury a terrorist attack. Did it get him killed? By Dexter Filkins

Alberto Nisman accused Iran and Argentina of colluding to bury a terrorist attack. Did it get him killed? By Dexter Filkins

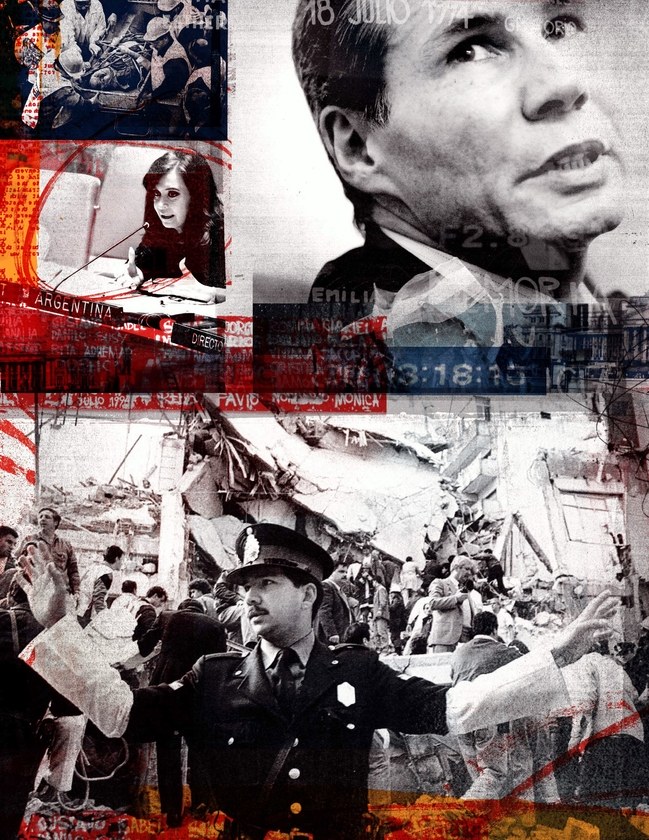

In the last days of his life, Alberto Nisman could hardly wait to confront his enemies. On January 14th of this year, Nisman, a career prosecutor in Argentina, had made an electrifying accusation against the country’s President, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. He charged that she had orchestrated a secret plan to scuttle the investigation of the bloodiest terrorist attack in Argentina’s history: the 1994 suicide bombing of the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina, the country’s largest Jewish organization, in which eighty-five people were killed and more than three hundred wounded. Nisman, a vain, meticulous fifty-one-year-old with a zest for Buenos Aires’ gaudy night life, had pursued the case for a decade, travelling frequently to the United States to get help from intelligence officials and from aides on Capitol Hill. In 2006, he indicted seven officials from the government of Iran, including its former President and Foreign Minister, whom he accused of planning and directing the attack, along with a senior leader of the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah. Months later, Nisman secured international arrest warrants for five officials, effectively preventing them from leaving Iran. As the case made him a celebrity, he invested in blue contact lenses and Botox injections. “Whenever he saw a camera, that was it, he would drop everything,” Roman Lejtman, a journalist who covered the investigation, said.

Over the years, the case, known by the Jewish organization’s acronym, amia, had exposed the flaws of Argentina’s judicial system. The presiding judge was indicted for trying to hijack its outcome, as were some of the country’s highest-ranked politicians. Iran’s leaders scoffed at Argentina’s demands to extradite the accused, and even issued a warrant for Nisman’s arrest. Nisman persevered, pressing the Iranians at every opportunity. From the beginning, he had the unstinting support of Argentina’s Presidents—first of Néstor Kirchner, who chose Nisman to supervise the prosecution in 2004, then of Cristina, who succeeded her husband in 2007. Every autumn, she travelled to New York and denounced the Iranian regime before the United Nations. Whenever Iran’s President, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, entered the main hall to speak, Argentina’s diplomats, under Kirchner’s orders, walked out.

And then, in early 2013, Kirchner, known for her erratic manner and ruthless political acumen, made an extraordinary about-face. Following months of clandestine negotiations, she struck a deal with the Iranian government that would, she said, finally break the deadlock over the amia case. The deal called for the establishment of a “truth commission” that would allow Argentine judges to travel to Tehran and possibly interview the suspects.

While many Argentines applauded Kirchner’s diplomacy, Nisman told friends that she had betrayed him by making a deal with the Iranians. Secretly, he embarked on another investigation, of Kirchner herself. On January 14, 2015, Nisman released the results, accusing the President of engaging in a criminal conspiracy to bury the amia case. “The order to execute the crime came directly and personally from the President of the Nation,” he wrote. Amid a public outcry, Nisman was summoned to testify before the Argentine Congress. He told friends that he’d begun to fear for his life, but he was determined to see the case through. A few days before his scheduled appearance, he sent a text message to a friend: “On Monday I am going in strong with evidence!”

The night before Nisman was due in Congress, his body was found in his apartment, slumped against the bathroom door in a pool of blood. There was a bullet hole in his head and, on the floor next to his hand, a .22-calibre pistol and the casing from a bullet. In a trash can, police found a draft of a legal document, written by Nisman and never executed, clearing the way for Kirchner’s arrest.

Over the next few weeks, every Argentine seemed to have an opinion about how Nisman had died; the case became the Latin-American equivalent of the J.F.K. assassination, grist for conspiracy theories involving spies and foreign governments and conniving politicians. Posters across Buenos Aires asked, “Who killed Nisman?”

During the investigation, Nisman had received many death threats, but his friends say that he bore them lightly. At one point, an Israeli writer named Gustavo Perednik met with Nisman in a Buenos Aires café to discuss what he should name the book he was completing about the amia case. Perednik passed Nisman a list of potential titles. He picked one immediately: “The Assassination of Alberto Nisman.” “Very catchy!” Nisman said.

On the morning of July 18, 1994, a man driving a Renault utility truck loaded with several hundred pounds of ammonium nitrate and TNT pulled up to the building that housed amia and detonated his payload. The six-story structure collapsed, leaving behind a scene of corpses, severed limbs, and wailing victims. Rescue workers spent weeks searching the rubble for bodies and survivors.

The attack followed a nearly identical one two years earlier, in which a truck bomb exploded outside the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires, killing twenty-nine people and wounding two hundred and forty-two. A wing of Hezbollah claimed responsibility, and many American officials believed that the Iranian regime had approved and helped carry out the attack. In the amia bombing, too, they suspected that Iran and Hezbollah, which often act together, were the main culprits.

The Argentine government began an investigation, but it soon stalled. The police recovered parts of the Renault truck—and then allowed them to sit in a warehouse. Three years into the investigation, James Bernazzani, a senior agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, was dispatched to Buenos Aires to help. When he and his team began examining the truck, they found bits of flesh and bluejeans stuck to a fragment of metal. Technicians at an F.B.I. lab quickly identified a man who they believed was the driver: Ibrahim Hussein Berro, a Hezbollah operative from Lebanon. Intelligence analysts determined that Berro’s family had been fêted by Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s leader, shortly after the bombing. “The case we made would have stood up in the U.S. judicial system,” Bernazzani said.

But the Argentine prosecutors decided to focus instead on what they called the “local connection”: twenty-two Argentines, including a number of police officers who they said had assisted in the attack. At the center of the case was a member of a local stolen-car ring named Carlos Alberto Telleldin, whom they accused of selling the Renault to the bombers.

At first, Telleldin claimed to have sold the truck to a man with a Central American accent, but he soon changed his story to implicate police officers from Buenos Aires Province. Not long afterward, a video surfaced that explained the reversal. The video, aired on national television, showed the judge in the case, Juan Galeano, paying Telleldin four hundred thousand dollars and instructing him to accuse the police. According to prosecutors, the country’s President, Carlos Menem, had endorsed the bribe, possibly in an effort to embarrass the governor of Buenos Aires, a political opponent. “In Argentina, large court cases are not about themselves,” Pablo Jacoby, a lawyer for a group of amia survivors and victims’ families, told me. “They are used by politicians to settle their differences.”

As the case wound through Argentina’s labyrinthine judicial system, absurdities multiplied. A fireman admitted in court that he had lied about finding a piece of the truck which had actually been discovered by an Israeli investigator. A lawyer who worked on the case said that he had been tortured by Argentine intelligence agents and interrogated about tapes of Iranians involved in the plot. “Every aspect of the case was a disaster, beginning with the initial investigation,” Claudio Grossman, who was dispatched by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to observe the trial, said. (He is now the dean of American University Law School.) “Argentina is a modern country, but there is no trust in the legal system, no faith that the system can solve problems.”

In 2003, the prosecution finally collapsed, with a court finding all twenty-two defendants not guilty. Judge Galeano, Menem, and the head of the country’s main intelligence agency, side, were prosecuted. By the time the trial was over, it had compiled five hundred and eighty-eight volumes of evidence, heard twelve hundred and eighty-four witnesses, and lasted for nine years, making it the longest-running case in Argentine history. Néstor Kirchner, elected President that year, called the government’s handling of the case “a national disgrace.”

A year later, Kirchner selected Nisman, then a junior prosecutor, to salvage what he could from the disastrous case and try again. Nisman was a surprising choice: he had been part of the team that led the initial amiaprosecution, which carried on despite overwhelming evidence that the case had been corrupted. “I had lost respect for him,” Alejandro Rua, who worked on the prosecution, said. “He knew the case was bad, but he kept going.” Nisman’s friends saw it differently: as a junior lawyer, he had no choice but to go along.

Even as a young prosecutor, in the provincial city of Olivos, Nisman was smart and ambitious and unabashed about showing it. In the courtroom, he talked so fast that judges sometimes had trouble understanding him. He had started working in the judicial system at age seventeen, as an unpaid clerk, telling friends that one day he’d be attorney general. “We were the youngest people in the country doing the job then,” Fabiana León, a friend from those days, said. “Alberto did not like to lose, so he’d fight a lot with the judges, always objecting and making appeals.”

Two years after taking over the amia case, Nisman produced an indictment. In the course of eight hundred and one pages, he charged seven Iranian officials, including the former President, Ali Akbar Rafsanjani, and also indicted Hezbollah’s senior military commander, Imad Mugniyah. “The decision to carry out the attack was made not by a small splinter group of extremist Islamic officials,” Nisman wrote, but was “extensively discussed and ultimately adopted by a consensus of the highest representatives of the Iranian government.” Drawing on the testimony of Iranian defectors, Nisman wrote that the decision was made on August 14, 1993, at a meeting of the Committee for Special Operations, which included the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei.

Since the nineteen-eighties, Nisman wrote, Iran had established a “vast spy network” inside Argentina that gathered information, picked targets, and recruited local helpers. The coördinator of the amia operation inside the country was an Iranian named Mohsen Rabbani, who for many years was a leader at a mosque in Buenos Aires called Al Tawhid. It was Rabbani, Nisman said, who financed the attack, oversaw the purchase of the Renault, and directed the assembly of the bomb.

Nisman tracked the movements and telephone conversations of Rabbani and others in the days and hours leading up to the attack, showing that most of the plotters were talking to one another and to the Iranian Embassy in Buenos Aires. Nearly all of them left Argentina before the bombing, as did the Iranian Ambassadors to Argentina and several neighboring countries. But Rabbani stayed behind. He had recently been appointed a cultural attaché at the Iranian Embassy, and was thus the beneficiary of diplomatic immunity. Remarkably, he remained in Argentina for three more years, proclaiming his innocence, and was never taken into custody. In a statement after the bombing, Khamenei seemed to praise the attack: “By gathering together groups of Jews with records of murder, theft, wickedness, and hooliganism from throughout the world, the Zionist regime has created an entity under the name of the Israeli nation that only understands the logic of terror and crimes.”

Despite all the detail that Nisman gathered, the question of Iran’s motive was never definitively answered. Israeli officials believe that the bombing was meant to avenge an Israeli attack on a Hezbollah training camp in Lebanon a month earlier. But, according to Matthew Levitt, a former senior Treasury official and the author of a book on Hezbollah, planning for the amiaoperation began months before the Lebanon attack took place.

Much of the testimony that guided Nisman toward the Iranian regime was provided by a man referred to in court documents as “Witness C”—Abolghasem Mesbahi, an Iranian intelligence agent who defected to Germany in 1996. Mesbahi, too, was vague about Iran’s motivations. He told investigators only that the regime regarded Argentina, whose Jewish population is the seventh-largest in the world, as an easy place to kill Jews. But he offered one clear explanation for the vexed legal process that followed: President Menem, he claimed, was a paid Iranian asset of long standing.

For years leading up to the attack, Middle Eastern countries had sought to expand their influence in Argentina. Menem’s predecessor, Raúl Alfonsín, had cultivated relationships with Egypt and Iraq, collaborating on a medium-range ballistic missile called the Condor. Alfonsín’s government had also agreed to provide material and technical assistance to Iran’s nuclear program, which was beginning to raise concerns in the West.

According to Mesbahi, Menem began receiving large sums of money from Iranian agents in the mid-eighties, when he was the governor of La Rioja Province. Menem is of Syrian descent, and the payments, usually made to companies that he was connected with, were intended to buy influence in the country’s Middle Eastern community. According to a former senior member of his Administration, Menem also received millions of dollars from other governments, including those of Muammar Qaddafi, in Libya, and Hafez Assad, in Syria, to pay for his election campaigns.

Yet after Menem was elected President, in 1989, he halted arms deals with Libya and Syria and annulled the nuclear accord with Iran, according to Domingo Cavallo, his Foreign Minister. “The Americans told us, If you want to have a good relationship with us, cancel the agreement with the Iranians,” Cavallo explained. “So we did.” In Nisman’s telling, the cancellation of the nuclear agreement had prompted Iran to attack the amia center. He noted that, at the time, Iran was pressing Argentina to resume the agreement, but he offered little other evidence to support the allegation.

Mesbahi suggested that Menem’s clandestine relationship with Iran continued through the amia bombing. Under interrogation, he claimed that Menem had agreed to whitewash Iran’s role, and in exchange received ten million dollars, wired to his numbered account at the Bank of Luxembourg in Geneva. The money was paid from another Swiss account, controlled by Rafsanjani, the Iranian President. The F.B.I. agent Bernazzani argued that a formerly credible defector was peddling bad information. “Mesbahi was full of shit,” he said. Still, many American officials believe that Iran was involved in the bombing. Hezbollah would never carry out such an operation without Iran’s approval, they said. “The assumption was that the Iranians were involved, because the attack was carried out by a unit that they created,’’ Robert Baer, a former American intelligence official who tracked links between Hezbollah and Iran, said. “Mugniyah never did anything without the green light of the Supreme Leader.”

In 2007, Interpol’s general assembly endorsed Nisman’s indictment and issued “red notices” for five Iranian officials, calling on member states to arrest them. Interpol declined to issue warrants for the former Iranian President, Foreign Minister, and Ambassador—not because the proof did not merit them but because the agency’s bylaws prevent it from pursuing national leaders.

In the years that Nisman presided over the amia investigation, he became a famous man. Separated from his wife, he was a fixture at Buenos Aires’ night clubs and sometimes appeared in gossip magazines with various girlfriends. He relished his image as a lone prosecutor going after terrorists in the Middle East. With a large staff and a big budget, he cultivated relationships with American intelligence analysts, conservative think-tank experts, and the staff of Senator Marco Rubio, who kept track of his work. He rented a luxury apartment in the chic neighborhood of Puerto Madero and indulged a passion for windsurfing. Claudio Rabinovitch, a co-worker and a friend since high school, recalled, “He told me, ‘Claudio, we are fifty years old, and it’s time to enjoy our lives!’ ”

Yet Nisman remained intensely committed to his work and to his daughters, Iara and Kala, talking to them on the phone several times a day. After his father died, in 2004, he began to stay home from the office on Yom Kippur. It was a rare break. According to friends, the amia case had become a fixation: year after year, despite the lack of progress, Nisman kept searching for ways to hold the Iranians accountable. “Sometimes he would call me at two in the morning and tell me to be at the office at sunrise,” Diego Lagomarsino, a computer technician who worked for him, said. “Nothing Alberto did was surprising.”

Nisman seemed to carry all the case’s complexities in his head. “It was unbelievable how he remembered every detail, precise dates and facts,” Rabinovitch said. In his home and office, nothing was out of place. Papers were stacked at tidy right angles; not a trace of dust could be seen anywhere. In a country famous for steak and wine, Nisman ate rice crackers and barely touched alcohol. He went to lunch several times a week at Itamae, a sushi restaurant around the corner from his apartment—always the same meal, eaten with chopsticks held together by a rubber band.

As Nisman assembled his case, he cultivated a friendship with Jaime Stiuso, a senior official at side. Stiuso, then in his late fifties, was a shadowy figure; he’d joined the agency in the nineteen-seventies, when side was heavily involved in repression and torture. In the years since, he’d almost never shown himself in public. But, according to Juan Martín Mena, a highly placed Argentine intelligence official, “Stiuso was the dominant force in the agency.”

Nisman also got assistance from the United States. According to diplomatic cables obtained by WikiLeaks, American officials gave him guidance, helped him draft legal briefs, and lobbied foreign governments to support him. Between 2006 and 2010, Nisman met with U.S. Embassy officials more than ten times, at least once to speak with a senior official from the F.B.I. On one occasion, Nisman apologized for not telling the Embassy in advance that he had recommended Menem’s arrest. It’s unclear to what extent Nisman received help from American intelligence officers, but his visits to the Embassy fuelled speculation in the Argentine press that he was a puppet, dutifully following American and Israeli orders.

Despite the many death threats he received—in phone calls, letters, and e-mails, many of them directed at his daughters—Nisman believed that his connections in side would keep him safe. The Argentine government gave him a round-the-clock team of bodyguards. Nisman often dispatched them to run errands, leaving himself unprotected.

For years, Nisman had no greater supporter than Cristina Kirchner. Every September, when she travelled to New York for the opening of the General Assembly of the United Nations, she brought a group of amia survivors with her. In 2011, she told the assembly, “I am demanding, on the basis of the requirements of Argentine justice, that the Islamic Republic of Iran submit to the legal authority and in particular allow for those who have been accused of some level of participation in the amiaattack to be brought to justice.”

Kirchner and her husband had long presented themselves as the moral censors of the country, leading an unprecedented effort to confront Argentina’s history of political violence. From 1976 until 1983, during a period dubbed the Dirty War, military dictators carried out a brutal campaign against suspected guerrillas and their sympathizers. The purge swept up students, professors, newspaper editors, and priests and nuns. Suspects were kidnapped, interrogated, and tortured, and many were flown over the Río de la Plata and thrown into the water. In this way, as many as thirty thousand Argentines were “disappeared.”

The military regime collapsed in 1983, following Argentina’s humiliating defeat in the Falklands War, but for decades the country’s civilian leaders largely refrained from investigating the crimes of the past. Each week, the mothers of people who had been disappeared gathered in front of the Presidential palace in silent protest. After Néstor Kirchner was elected, in 2003, he walked into the Naval Military College and demanded that portraits of the military leaders in the lobby be removed. On another occasion, standing before an assembly of officers, he announced, “I want to make it clear, as President of this nation, I am not afraid of you.” Some of the generals walked out. In 2005, Kirchner supported the repeal of two amnesty laws, and he instructed prosecutors to begin investigating.

Néstor and Cristina were young, colorful, and smart; former law-school sweethearts, they prompted comparison to Bill and Hillary Clinton. In 2007, Néstor announced that he would stand aside to allow Cristina, then a senator, to run for President. After taking office, Cristina presided over the convictions of hundreds of officers for murder and torture. “What Néstor began, Cristina continued,” Raúl Zaffaroni, a former justice of the supreme court, told me.

Kirchner proved to be a dramatic and polarizing leader. “Fear God,” she said at a cabinet meeting in 2012, “and a little bit me.” According to local lore, while Néstor was President, he got into a heated argument with one of his ministers during a dinner at the official residence, prompting the minister to storm out. When Néstor chased the minister in a golf cart and coaxed him back to the table, Cristina ordered him out again, saying, “He who stands up once from my table will never sit with us again.”

In confidential cables released by WikiLeaks, American diplomats noted Kirchner’s “aggressive demeanor” and her apparent obsession with her looks. She reportedly spent “thousands of dollars every year on the latest fashion and having silicone injections in her face and hair extensions to make her appear younger.” The media gave her the nickname Botox Queen, and Kirchner sometimes played along, telling interviewers, “I was born in makeup.” In 2012, she displayed a surgical scar in a press conference and explained, “You know how I can be with aesthetics”—a play on a Spanish term for plastic surgery. “Politics before aesthetics.”

Néstor had taken office in the middle of an economic collapse, with more than half of all Argentines living in poverty. He chose an unorthodox strategy, emphasizing growth, even at the price of inflation, a devalued currency, and the risk of another collapse. Cristina kept up his efforts, nationalizing the country’s main airline and a large oil and gas company and seizing control of billions of dollars in private pension funds. She spent heavily on the problems of the poor, initiating a universal child-benefit plan and increasing pension payments for the elderly. Most notably, she continued her husband’s aggressive approach to Argentina’s debt, which amounted to nearly a hundred billion dollars. After laborious negotiations, a majority of bondholders agreed to accept a buyout of about thirty-three cents on the dollar.

In the view of many economists, this program carried the risk of crippling economic problems, forcing Argentina to make deals with China to bolster its foreign reserves. “Kirchner’s strategy has been a series of short-term fixes, none of which is sustainable,” Arturo Porzecanski, a professor of economics at American University, told me. “The model is nearing exhaustion.” A number of bondholders, mostly American hedge funds, continue to insist that they should be repaid in full. Kirchner has refused, referring to them as “vultures,” and the dispute has led to some extraordinary moments. In 2012, an Argentine naval vessel was seized at a Ghanaian port on one creditor’s request; the ship was released by a court order. The next year, Kirchner hired a private jet for a weeklong tour of Asia—at a cost of eight hundred and eighty thousand dollars—for fear that creditors would seize the Presidential plane.

Kirchner has prompted growing comparisons to Hugo Chávez, the populist and authoritarian President of Venezuela from 1999 until his death, in 2013. Indeed, both Kirchners grew dependent on Chávez, especially after Venezuela purchased seven billion dollars’ worth of Argentine debt as the country was emerging from its economic crisis. Venezuelan money may have been instrumental in Cristina Kirchner’s election. In 2007, Argentine customs officers scanning luggage from a chartered jet from Caracas found eight hundred thousand dollars stuffed in a suitcase. Its owner, Guido Antonini Wilson, told the F.B.I. that the cash was part of a Chávez-directed effort to finance Kirchner’s campaign.

Cristina Kirchner visited Chávez in Caracas and voiced support for his maverick foreign policy, warming to authoritarian states like China, Russia, and Cuba. Kirchner has at times blamed the United States for her country’s problems, describing it as a “hegemonic world power.” Last year, after an American court issued an unfavorable ruling regarding Argentina’s foreign debt, Kirchner seemed to allude to her own assassination. “If something happens to me,” she said, “look north.”

Over time, Kirchner has grown more dictatorial and, according to muckraking reports, more corrupt. The Clarin media empire, her greatest antagonist, has published a series of compelling (if not error-free) stories about the Kirchners’ dealings with businessmen, as well as the spectacular increase in their personal wealth during their time in office. After a series of confrontations with the press, Kirchner began to deprive some media institutions of state advertising. In 2009, she introduced “reform” legislation that seemed tailored to dismantle Clarin. “She is trying to destroy us,” Martín Etchevers, Clarin’s communications director, told me. Under Néstor Kirchner, a prosecutor named Manuel Garrido was appointed to investigate corruption in the Argentine government. When Cristina curbed his powers, he resigned in protest. He later told the Wall Street Journal that the scandals around Kirchner “mirror the emergence of crony capitalism, oligarchs who rose during the past decade through their ties to government officials.”

One matter on which Kirchner appeared steadfast was the amia bombing. But, after Néstor died, in 2010, and she won a landslide reëlection the next year, her stance shifted. When Kirchner travelled to the United Nations that year, she responded favorably to an Iranian offer to “investigate” the amia bombing. When Ahmadinejad rose to speak, Argentina’s delegates remained in their seats. And for the first time in years the survivors of the bombing stayed home.

On January 27, 2013, Kirchner announced that she had struck an agreement with Iran to set up the truth commission. The agreement did not call for a trial of the Iranian suspects, and none of its findings would be binding. Still, Kirchner called the agreement “historic,” saying that it would help to finally resolve the case. On Twitter, she wrote, “We will never again let the amiatragedy be used as a chess piece in the game of foreign geopolitical interests.”

The agreement with Iran was negotiated by Héctor Timerman, Kirchner’s Foreign Minister. Timerman is a paradoxical figure in Argentine public life: a Jew who describes himself as a “non-Zionist” and a sharp critic of the United States who lived for a decade in New York. Like many of Argentina’s leading political figures, Timerman was shaped by his experience in the Dirty War. He is the son of Jacobo Timerman, a prominent newspaper editor, who was detained in 1977 and tortured in a secret prison; his account of the ordeal, “Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number,” was an international best-seller. With his father in jail, Héctor Timerman fled to New York, where he lived in the West Village and helped found the human-rights organization Americas Watch. In 1989, he returned to Argentina to work as a journalist. In 2004, he came back to New York as part of Argentina’s delegation to the U.N., and in 2007 he went to Washington as Ambassador.

Timerman told me that he negotiated with his Iranian counterpart, Ali Akbar Salehi, in a series of secret meetings; over three months, beginning in September, 2012, they met in Zurich and Addis Ababa. He said that they faced an intractable legal problem. The Iranian constitution prohibits extraditing criminal suspects, and the Argentine constitution prohibits trying the Iranians in absentia. With no hope of resolving the case through standard legal channels, Timerman wanted to find some way of holding the perpetrators accountable. The truth commission would at least allow Argentine judges to go to Tehran and possibly interview the suspects. “We were going to tell them, ‘These are the charges against you,’ ” Timerman said. “You can’t go to the end of the trial, but you can start it.”

The agreement created a national uproar. Some Argentine Jews accused Kirchner of surrendering to the Iranians; many objected to the term “truth commission,” which suggested that the perpetrators of the attack were unknown. (Even Timerman conceded that it was a “terrible name.”) Doubts arose about Timerman’s explanation, especially his contention that he had been talking to the Iranians for only a few months. Nisman declared that the agreement represented an “unconstitutional” intrusion by the President into the judiciary and, in a televised interview, insisted that the Iranian suspects be brought to trial in Argentina, saying, “These crimes can be judged only where they happened.” In private, Nisman told friends that he suspected there was more to the deal with Iran than Kirchner was letting on. Recalling that time, his friend Fabiana León said, “Alberto is on fire.”

Shortly afterward, Nisman began investigating Kirchner and Timerman, with help from Stiuso, the senior intelligence official. He kept his activities secret, even from some people in his office. One person he confided in was Perednik, the Israeli writer. “He didn’t tell me all the details,” Perednik said. “But he was very excited. He said that by the time this was over Kirchner and Timerman were going to jail.”

On January 12th, Nisman, on vacation in Europe with his daughter Kala, sent a text message to friends, saying that he was cutting his trip short and flying to Buenos Aires. “I have been preparing for this for a long time but I didn’t imagine it would happen so soon,” Nisman wrote. “I am putting a lot at stake with this. Everything, I would say.” He came back so abruptly that he left his teen-age daughter in the Madrid airport, waiting for her mother to pick her up.

Nisman didn’t say what he was planning—“Some may know what I am talking about, others may imagine”—but the implication must have been clear. A month before, Kirchner had peremptorily sacked three top intelligence officials, including Nisman’s ally Stiuso. Argentine Presidents are immune from prosecution while in office, but Kirchner’s term was due to end in a year. People speculated that she fired them to protect herself from an investigation. “Nisman thought he was next,” Fernando Oz, a journalist who spoke with Nisman regularly, said. “He thought if he waited any longer he wouldn’t have a job and he wouldn’t be able to accuse her.” His team would be disbanded, and he would have nothing to show for a decade of highly paid and highly publicized work.

In his messages to friends, Nisman wrote, “I know it won’t be easy. But earlier than late the truth prevails.” He signed off, “In case you’re having doubts, I’m not crazy or anything like that. Despite everything, I’m better than ever hahahahahaha.” On the morning of January 14th, just hours after his return, Nisman hand-delivered a two-hundred-and-eighty-nine-page report to a federal judge and made a sixty-page summary available to the media. He accused Kirchner and Timerman of “being authors and accomplices of an aggravated cover-up and obstruction of justice regarding the Iranians accused of the amia terrorist attack.” It was not an indictment but a call for further investigation. Among other things, Nisman wanted to interrogate the President.

The report’s central argument is that, in addition to the public agreement to set up a truth commission, there was a secret agreement, in which the Argentine government would remove the Iranian names from Interpol’s wanted list. In exchange, Argentina would benefit from lucrative agreements to sell grain and buy Iranian oil, or possibly to trade them. To make the deal acceptable to the public, Nisman said, Kirchner and Timerman planned tocome up with a “new theory” of who committed the amia bombing.

The scenario closely aligned with one laid out four years earlier by the Argentine journalist Pepe Eliaschev, who had written that Timerman passed a message to Iran saying that Argentina was ready to “forget” the amia bombing, as well as the 1992 attack on the Embassy. Eliaschev claimed to have a copy of a memorandum that Iran’s Foreign Minister gave to President Ahmadinejad, saying, “Argentina is no longer interested in solving these two attacks, but instead prefers to improve economic relations with Iran.”

The Iranian government was a growing force in the region. According to former Venezuelan officials, Hugo Chávez introduced Ahmadinejad to leaders throughout Latin America. Among other things, Iran and Venezuela had established a weekly flight between Caracas and Tehran, and the two governments had set up a two-billion-dollar fund for investments in both countries. American officials say that Chávez also granted safe haven to operatives from the Iranian Revolutionary Guards and from Hezbollah. In 2007, Chávez agreed to allow Iran and Hezbollah to use Venezuela as the base for a drug-trafficking and money-laundering network, according to a former American official who worked on narco-terrorism investigations. The official told me that the network netted the Iranians and Hezbollah as much as a billion dollars a year, with the Caracas-Tehran flights often being used to ferry drugs.

As Cristina Kirchner solidified her relationship with Chávez, Argentina grew closer to Iran. During her first term, trade between the two countries doubled, with Iranians buying large quantities of Argentine grain. In early 2012, when the International Monetary Fund threatened to impose sanctions on Argentina for lying about its inflation rate, Héctor Timerman travelled to Washington to discuss the matter with the Obama Administration. According to an American official who was at the meeting, Timerman asked the White House to pressure the I.M.F. to rescind the warning. When the White House declined, the official recalled, Timerman mentioned the international effort to stop Iran from building a nuclear weapon and suggested that his government was considering taking Iran’s side. (Timerman denies making such a statement.) “When Héctor said that, you could have heard a pin drop in the room,” Dan Restrepo, an assistant national-security adviser at the time, told me.

In Nisman’s view, Kirchner and Timerman were so eager to strengthen their alliance with Iran that they were willing to sacrifice national sovereignty. “Let there be no doubt,” Nisman wrote. “The criminal plan consisted of eliminating the charges that the Argentine courts had filed against the Iranian officials, and the best means that was found to clear those charges, provide immunity and portray the matter in the tidiest possible manner to a deceived nation was to sign the aforementioned agreement.”

Nisman accused Kirchner of carrying out the scheme by a back channel involving civilians close to both governments. The heart of his accusation is a series of transcripts of recorded telephone conversations, many of which involve two Argentine activists, Luis D’Elía and Fernando Esteche. Both are fervent Kirchner supporters, have travelled repeatedly to Iran, and have led pro-Iranian demonstrations, in which they said that Iran was not responsible for the amia bombing. According to a Western diplomat in Buenos Aires, D’Elía—a former housing official in Néstor Kirchner’s government—is funded by the Iranian government.

In Nisman’s account, the two men—along with Andres Larroque, a member of the Argentine Congress—worked as Kirchner’s emissaries. Most of the wiretapped conversations feature them talking to Yussuf Khalil, a Lebanese-Argentine with ties to the Al Tawhid Mosque in Buenos Aires, where much of the attack on amia was said to have been coördinated. The mosque remains a gathering spot for anti-Israeli and pro-Iranian demonstrations; D’Elía and Esteche have both spoken there. According to Nisman, Khalil acted as an agent of the Iranian government and stayed in close touch with officials in Tehran.

Nisman’s report, evidently assembled in haste, is a rambling and sometimes maddening document. Although Nisman accused Kirchner of directing the secret deal and Timerman of carrying it out, there is no evidence tying either one of them directly to the alleged conspiracy. Most of the wiretapped conversations are cryptic and could be interpreted in ways that are not necessarily incriminating. Still, the accretion of detail and circumstance suggests that the men were discussing some kind of deal designed to lead to the removal of the Iranians from Interpol’s wanted list.

The most mysterious figure in the transcripts is someone known only as Allan; according to Nisman, he is Ramón Allan Héctor Bogado, an intelligence agent who works directly for Kirchner. (Mena, the senior intelligence official, told me that there is no record of Bogado’s ever having been employed by side. But an Argentine news Web site later published a statement from someone claiming to be Bogado, who said that he had worked for the agency as an “inorganic,” an agent who works off the books.) In February, 2013, a month after the Argentine government announced the agreement for the truth commission, Bogado talked with Khalil, the presumed Iranian operative. “I have gossip,” Bogado said. “I was told there at the house Interpol will lift our friends’ arrest warrants.” Khalil responded, “Thank goodness!”

“Don’t worry,” Bogado says in another conversation with Khalil. “All this has been agreed to at the very top.”

In a transcript from that May, D’Elía tells Khalil that he is acting on orders from the “boss woman,” and that the Argentine government was preparing to send the two of them, along with a contingent from the national oil company, to Iran in order “to do some deals there.” D’Elía had apparently just met Julio de Vido, the Minister of Planning. “He’s very interested in exchanging what they have there for grains and beef,” D’Elía says.

The proposed trade deals were evidently linked to the Iranian parliament’s ratification of the public pact, which is commonly referred to as the “memorandum.” D’Elía suggests that this is a source of trouble. “There’s a political problem,” he says. “They need the memorandum to be approved, right?”

“Yes,” Khalil responds. “This subject is quite clear.”

In conversations recorded before the public pact was announced, some of the men in the transcripts seem to have inside knowledge of the negotiations. In December, 2012, a month before the announcement, Esteche told Khalil that Kirchner’s government intended to invent a culprit for the bombing. “They want to construct a new enemy of the amia, someone new to be responsible,” he said. “They aren’t going to be able to say it was the Israelis,” he continued. Instead, the blame would be placed on a “group of local fascists.”

Bogado said much the same thing, months after the agreement between Iran and Argentina was signed: “There is going to be another theory with other evidence.” Bogado seemed to suggest that Nisman, despite his commitment to pursuing the Iranians, would be marginalized: “He’ll be twisting in the wind.”

President Kirchner works in an ornate mansion in central Buenos Aires known as “the Pink House”—for the tint of its walls, once supplied by horse blood—but her official residence, in a northern suburb, is called Quinta de Olivos. Dating to the sixteenth century, Olivos, as it is known, is a white three-storied palace that resembles an enormous wedding cake.

When I met Kirchner there, two months after Nisman died, the mystery was still dominating the news. I was ushered into a wide split-level room that had been set up as a television studio. Kirchner entered a few minutes later, in a flouncy dress and heavy makeup, followed by two dozen aides, nearly all of them men. With the cameras running, Kirchner reached over, before the interview began, to fix my hair. “Is there some girl who can help him with his hair?” she asked. “We want you to be pretty.” Then she began to straighten her own. “I want to primp myself a bit,” she said. “Excuse me, I’m a woman, besides being the President: the dress, the image—”

“Divine!” one of her aides called from off the set.

Once we started talking, Kirchner turned serious, deriding Nisman’s accusation that she had made a secret deal to forget the amia attack; she called it “ridiculous,” “not serious,” and an “indictment without any kind of evidence.”

Kirchner told me that she believed Iran was probably involved in the attack, and that she had always insisted that the regime turn over the suspects. But after twenty-one years it was clear that the Iranians were never going to do that. “They never answered anything,” Kirchner said. “We were at a dead end.” She said that setting up the truth commission could allow an Argentine judge to question the Iranian suspects, and she described it as an important achievement: “We succeeded in persuading Iran to agree to have a discussion about the amia issue when they had refused it for decades.”

Members of Kirchner’s government have unanimously rejected Nisman’s accusations; the cabinet chief, Jorge Capitanich, called them “absurd, illogical, irrational.” Timerman denied making a secret deal and claimed that he doesn’t even know the people listed in the complaint. “Who is this Khalil?” he said. “Why doesn’t someone go and find him?”

Soon after Iran and Argentina signed their public agreement, Interpol released a statement saying that the arrest warrants would remain in place. The Iranian parliament declined to ratify the deal. Khalil, in the transcripts, seemed enraged. He told D’Elía that he had met with “the highest authorities” in Iran and added, apparently referring to Timerman, “I think that Russian shit screwed up.”

For Nisman, the implication was clear: Timerman had promised that the notices would be lifted and when they were not the Iranians backed out. In his report, he notes that Salehi, the Foreign Minister, alluded to a secret agreement after the public one was signed. “The content of the agreement between Iran and Argentina in connection with the amia incident will be made public at the right time, and the matter of the accused Iranians is a part of it,” he said.

What went wrong? Nisman believed that Timerman was planning to ask Interpol to lift the red notices. But Ron Noble, the head of Interpol at the time, told me that Timerman had asked on several occasions for the notices to be left in place. In any case, if Timerman had wanted the notices voided he would have needed an Argentine judge to dismiss the related charges. Noble pointed out that Interpol couldn’t act until those charges were dropped. Kirchner, too, emphasized that the disposition of the red notices wasn’t in her hands. “I could have publicly signed for the Iranians here in front of the whole world,” she said, “and it has no value.”

Then what were Khalil and the others talking about? Timerman told me that it’s possible they believed that the red notices would be lifted but were themselves playing no part in it. He suggested that they were just opportunists trying to capitalize on the warming relations between the two countries. “Maybe they were hoping they would get some business deals,” he said.

But this doesn’t explain their apparent conversations with officials in both governments, many of whom expressed advance knowledge of the deal. And it doesn’t explain a series of public statements about the agreement, which make up some of Nisman’s most intriguing evidence. His report points out that, in one of the final paragraphs of the pact, Timerman and Salehi agreed to a cryptic clause: “The agreement, upon its signature, will be jointly sent by both ministries to the Secretary General of Interpol as a fulfillment of Interpol requirements regarding this case.” That sentence is ambiguous, but it suggests that both countries expected some action from Interpol. The Iranian regime announced its expectation clearly. After the pact was ratified, the government-sponsored news agency issued a statement: “According to the agreement signed by both countries, Interpol must lift the red notices against the Iranian authorities.”

After Nisman filed his report with the federal judge, he visited Patricia Bullrich, a member of Congress and a leader of the opposition. As they discussed the allegations, Bullrich began to fear that Nisman was heading alone into a political hurricane. “He was going to be destroyed by the President,” she told me. Bullrich, the chair of the Criminal Legislation Committee, suggested a hearing, thinking that publicity would give him some protection. She told me that Nisman had left her office in high spirits, eager for a fight.

Word about the hearing spread quickly to Kirchner’s supporters. Diani Conti, a congresswoman from Kirchner’s party, said that she looked forward to confronting Nisman: “We’ve sharpened our knives.” Nisman spent his last days getting ready, and, at least outwardly, he was excited, nervous, and focussed. On Saturday evening, Waldo Wolff, a leader in Argentina’s Jewish community, sent a text: “How are you doing? What are you doing?” Nisman sent back a photo of a table filled with files and highlighter pens. “What do you think I’m doing?” he wrote. Claudio Rabinovitch, Nisman’s co-worker, saw him earlier that day. He told Nisman he was thinking about leaving his job, because he’d felt excluded from the secret investigation. Nisman, he said, refused to consider it. “Monday is the biggest day of my life,” he said.

At about four-thirty on Saturday afternoon, Nisman asked Diego Lagomarsino, his computer technician, to come over. When he arrived, Nisman told him that the reaction to his report was more intense than he’d anticipated. “I’m afraid to go out on the street,” he said; he had sent his mother to shop for groceries. Then he asked Lagomarsino, “Do you have a gun?”

Lagomarsino said he did, and Nisman asked to borrow it. Lagomarsino told me, “I got scared—I was shocked.” His gun, he told Nisman, was old and small, not worth bothering with. Nisman said he didn’t trust his bodyguards to protect him.

Lagomarsino said that Nisman began talking about his family and grew more upset. “Do you know what it’s like when your daughters don’t want to be with you because they’re afraid something might happen to them?” Nisman said. Lagomarsino told me, “I had never seen him like this.”

Nisman again asked Lagomarsino to bring him a gun. “I only need it to scare someone off,” he said. “If I’m in the car with the girls and a crazy guy with a stick comes up and says, ‘You traitor son of a bitch,’ I can shoot in the air and scare him away.”

Reluctantly, Lagomarsino said, he got the gun and brought it back. It was an old Bersa, .22 calibre, a gift from his uncle. Lagomarsino said he showed Nisman how to load the pistol, how to hold it, how to squeeze the trigger. Nisman agreed that it was not really up to the job of protecting him. “Next week, we’ll go buy a new one,” he said. Nisman took the pistol, wrapped in a green cloth, and told Lagomarsino that he could leave. Pointing at his files, he said, “I have to get back to this.”

I asked Lagomarsino if he had been worried that Nisman might kill himself. “No, no, no. Alberto? Never,” Lagomarsino said. “I was worried he was going to kill someone else.”

At about twelve-thirty on the afternoon of Sunday, January 18th, one of Nisman’s bodyguards called his phone and got no answer. The bodyguard grew increasingly concerned. After he knocked on the apartment door, with no response, he called Nisman’s mother, Sara Garfunkel. Nearly ten hours after the bodyguard called Nisman, Garfunkel and another bodyguard entered his apartment with the help of a locksmith. They found Nisman on the floor of the bathroom, with a bullet in his head and Lagomarsino’s pistol next to his hand. He’d written up a shopping list. He was wearing a T-shirt and shorts. An autopsy determined that Nisman had killed himself and that no one else had been in the apartment when he died. He’d left no note.

Two hours later, Damian Pachter, a journalist for the Buenos Aires Herald, wrote on Twitter that Nisman had been found in a pool of blood, not breathing. Four days later, Pachter noticed that his tweet had been quoted by the Web site for Télam, the state-controlled media agency—but that it had been altered, to read that Nisman had been found dead. “Maybe it was because I hadn’t slept, but I got really scared,” he said.

An old source advised Pachter to leave Buenos Aires and meet him in his home town, several hours outside the city. Pachter arrived before dawn and found a coffee shop that was open. While he waited for his source to meet him, he said, a man wearing sunglasses sat down next to him. Several hours passed, and the man sat quietly, ordering nothing. Finally, Pachter said, his source arrived and took a photo of the man. Pachter said, “That’s when I knew I had to get out of there.” He went immediately to a travel agency and bought a plane ticket to Israel, where he holds citizenship. While waiting for a connecting flight, he checked his e-mail. A newspaper editor in Israel had written to tell him that a copy of his plane ticket had been posted on the Twitter account of Kirchner’s office.

Pachter has not returned to Argentina, saying that he fears for his life. He said he doesn’t know for certain why he was being followed or why someone in Kirchner’s office had posted his flight details. Pachter believes that Nisman was murdered, and that some element of the Argentine state was probably involved. He thinks that after Nisman was shot the killers moved his body and then altered the scene to eliminate traces of their work. “I think when I tweeted they were working on something, improvising the crime scene,” he said.

In the weeks after Nisman’s death, Argentina boiled with conspiracy theories—blaming the C.I.A., Mossad, even British intelligence. Kirchner, on her Web site, endorsed the autopsy’s findings, saying that it was a “suicide.” Her allies insinuated that Nisman, faced with justifying a case he’d created out of thin air, had suffered a crisis of confidence.

Since the end of the Dirty War, one of the animating ideas of Argentine public life is that politics should not be lethal. As a popular saying has it, “The blood never reaches the river.” Even so, Argentina has a continuing history of “suicides” that have turned out to be political murders. In 2007, Héctor Febres, a naval officer accused of torturing pregnant women—suspected guerrilla sympathizers—and, after they gave birth, murdering them and turning their babies over to military families, was found dead in his prison cell of cyanide poisoning. His death was ruled a suicide, but many Argentines believe that he was either killed or forced to commit suicide by his former comrades in order to prevent him from informing on others.

Three days after Kirchner declared Nisman’s death a suicide, she reversed herself, saying that he had been murdered—in a plot to discredit her. “They used him while he was alive and then they needed him dead,” she wrote on her Web site, under the headline “The suicide (that I am convinced) was not suicide.” She didn’t say who “they” were, but a few days later Kirchner suggested that it was her own intelligence agency, side, and that therefore she would disband it and form another. The intelligence agency, she said, has “not served the interests of the country.”

It’s possible that Nisman succumbed to some private torment unknown to even those closest to him. Viviana Fein, a prosecutor charged with investigating Nisman’s death, left open the possibility that he could have been pressured into suicide—if, say, his daughters were being threatened. But among Nisman’s friends and professional acquaintances I could find no one who believed that he would shoot himself. “Alberto? Never,” León, his longtime friend, said. “He had fantastic self-esteem, and he really loved his children.”

Even after declaring Nisman’s death a murder, Kirchner allowed no sympathy for him. At a press conference, she suggested that he and Lagomarsino were lovers. She said that, as many had now suspected, she had fired the chiefs of side because they had opposed her agreement with Iran. Many Argentines did not believe her proclamations of innocence. In a nationwide poll commissioned the week after Nisman’s death, seventy per cent of those surveyed believed that he had been murdered, and half said they believed that the government was involved.

Basic facts about Nisman’s death remain unexplained. No gunpowder residue was found on his hand, as is typical of self-inflicted gunshots. His fingerprints were found on the pistol, but not those of Lagomarsino, who had just lent him the gun. A few days after the death, the police said that they had discovered a third entrance to Nisman’s apartment: a corridor for an air-conditioner that connects to a neighbor’s apartment; there they found an unidentified footprint. Police checked a camera mounted in the service elevator, and it was broken. In the stairwell, there were no cameras at all.

Evidence accumulated that the investigation into Nisman’s death had been so sloppy as to be fatally compromised. A woman summoned off the street to witness the crime-scene investigation (as required by Argentine law) described a partylike atmosphere. “They drank tea, ate croissants,” she said. “They touched everything. There were, like, fifty people in the apartment.” Police photos, provided to me by an Argentine journalist, show a group of police, without gloves, picking through Nisman’s belongings.

Nisman’s former wife, Sandra Arroyo Salgado, a powerful judge, denounced the investigation and engaged a leading forensics team to review the autopsy results. The team concluded that no muscular spasm had taken place in his right hand, as would have been normal if he had fired a gun, and that, in all likelihood, his body had been moved. (A police photo shows what are purported to be bloodstains on Nisman’s bed, suggesting that his body had indeed been moved.) According to the forensics team’s written report, which the newspaper La Nación obtained, stains in the bathroom sink had been scrubbed away, and the position of the gun was inconsistent with Nisman’s having shot himself. The most likely scenario, the report said, was that Nisman had been shot, while kneeling, in the rear-right of his head, and that he died in “agony.” At a press conference that Salgado held to announce the findings, she said, “His death is an assassination that demands a response from the country’s institutions.”

n February 18th, a month after Nisman’s death, tens of thousands of Argentines gathered to remember him and to protest what they described as the government’s failure to protect a prosecutor. In pouring rain, the demonstrators walked silently from the Argentine Congress to the Plaza de Mayo, in front of the building where Kirchner works. Many carried placards. One read, “You can’t suicide us all.” Kirchner accused the marchers of playing politics and stayed home. The next day, she celebrated her birthday. “In the Chinese horoscope,” she wrote on Twitter, “I am a snake.”

During my interview with Kirchner, she seemed unnerved by talking about Nisman’s death. When I raised the question of whether she’d had him killed, she blurted, “No!,” and then handed me a printout of the statement that she’d written for her Web site. She seemed mostly disturbed by the damage that Nisman’s death was doing to her reputation—which, she suggested, only strengthened the case that she hadn’t been involved. “Tell me, who has suffered the most with the death of prosecutor Alberto Nisman? You tell me, Sherlock Holmes.” When I suggested it was she—that half the country believed she was involved in Nisman’s death—she nodded. “Exactly. This is one of the keys.”

This view is widespread in Argentina, at least among Kirchner’s supporters. “Nisman’s case wasn’t that strong,” José Manuel Ugarte, a professor of law at the University of Buenos Aires, told me. “Kirchner would have survived it. I think the people who did this are people who wanted to destroy her government.”

Much of the early suspicion focussed on Jaime Stiuso, the senior official in side. Juan Martín Mena, whom Kirchner appointed to help lead the newly created intelligence agency, portrayed Stiuso as the leader of a rogue faction that was running a smuggling network. He said that senior members of side had a history of selling sensitive information to private buyers and of using such information to coerce results from reluctant judges.

Prosecutors say that on the last afternoon of Nisman’s life he tried repeatedly to call Stiuso, without success. They summoned Stiuso to answer questions and face embezzlement charges, but he vanished. One acquaintance of his said that he had fled to Uruguay; Kirchner thought that he was hiding in the United States.

Mena said that he did not believe that Nisman was involved in Stiuso’s illegal activities. So why did Nisman and Stiuso decide to work together against Kirchner’s outreach to Iran? Mena told me that, in their desire to keep the amia investigation going, the two men “followed foreign interests.” Which foreign interests? “The United States and Israel,” he said. “One hundred per cent.”

In the days before Nisman died, he believed that the Iranians were coming for him. When he met Bullrich, the congresswoman, he told her that he had overheard wiretapped conversations of Argentine military-intelligence officers saying they had passed his personal information to agents of Iran—on orders from Kirchner. Nisman said the Iranians knew “about him, about the investigation, with details about his family, about his daughters, about all the movements of his daughters.”

Since the Islamic Revolution, the Iranian regime has maintained an aggressive assassination program. The regime has been accused of murdering at least eighteen people living outside Iran, most of them Iranian dissidents. The most notorious murders took place in 1992, when Iranian agents gunned down four Kurdish exiles at a Greek restaurant in Berlin. In that case, German prosecutors had pursued Iranian officials relentlessly, much as Nisman did.

Yet no one in the Iranian regime seemed especially troubled by Nisman’s public allegations. And even if the regime wanted him dead why wait until after he gave his complaint to a federal judge? Many Argentines I talked with wondered whether he could have uncovered some other secret that caused someone in the Iranian—or the Argentine—government to kill him.

By the time Kirchner announced the agreement about the amia case, Nisman’s obsession with Iran had expanded beyond Argentina. That year, he and his staff produced a five-hundred-page report outlining what it said was Hezbollah’s and Iran’s terrorist “infiltration” in Latin America. (A U.S. official called the report “spot on.”) A month before Nisman died, he told the writer Gustavo Perednik that he believed Argentina and Iran could be secretly discussing renewing the nuclear agreement of the nineteen-eighties and nineties. “Nisman said this was part of the big deal,” Perednik told me.

In January, 2007, according to a former senior official in Chávez’s government, Ahmadinejad visited Caracas and asked Chávez to intercede with the Kirchners. The official, who attended the meeting, said that Ahmadinejad wanted access to Argentine nuclear technology. (The official is one of several who are coöperating with American investigators, building a case against Venezuela for helping smuggle drugs for Iran and Hezbollah.) Ahmadinejad didn’t specify what sort of technology he wanted. But the Iranian reactor in Arak, still under construction, uses similar technology to an Argentine reactor at Atucha. Both are heavy-water reactors capable of producing plutonium, which can be used in nuclear weapons. “Brother, I need a favor,” Ahmadinejad told Chávez, according to the official. “What it costs in terms of money, we will cover.”

“I’ll take care of it,” Chávez replied. Ahmadinejad also asked Chávez to persuade the Argentines to remove the Iranian names from the Interpol list. Chávez agreed to try.

The former Venezuelan official said that he did not know whether Chávez—or either of the Kirchners—acted on the request or, if so, what the Kirchners got in return. But Stiuso apparently shared Nisman’s suspicion that the deal was in process. He told Pablo Jacoby, the lawyer for the amia victims, that he was trying to make sure Argentina didn’t provide assistance to Iran’s nuclear program. “The real issue has always been the transfer of nuclear technology,” Jacoby said. “Stiuso told me he didn’t want the Iranians to get the bomb.”

In the months after Nisman’s death, his family asked to be left alone to grieve, so during his funeral, at the Jewish cemetery in the Buenos Aires suburb of La Tablada, hundreds of mourners gathered outside the gates. Some carried signs that said “We are all Nisman” or “No more corruption and impunity.” Others held Argentine flags or simply stood in silence. Inside, the Jewish community leader Waldo Wolff noted in a eulogy that Nisman’s death had revealed the inner workings of Argentine political power, which had failed to provide justice to the victims of the amia bombing for more than twenty years. “Alberto’s death, and the macabre plot around his death,” Wolff told the mourners, “came to remove the debris around the amia building, allowing us to see what actually lies underneath them: the dark labyrinth of power hidden in the most open parts of our society.”

As the weeks passed, the truth seemed as elusive as ever. A succession of judges, most of them loyal to Kirchner, dismissed Nisman’s complaint. Kirchner, though politically damaged, carried on. Jacoby told me that, with Nisman gone, the amia investigation—so complex, so divisive, so old—would probably die, too. “There is no replacement for Alberto,” Jacoby said. “The whole case is in his head.”

Suicide or murder? Jacoby said that that was the wrong question: “Now, even if the truth is that he committed suicide, nobody will ever believe it.” By Jewish tradition, people who kill themselves are sometimes denied a proper burial; in the cemetery in La Tablada, suicides have been relegated to a far corner. After some discussion, Nisman’s body was buried not with those who killed themselves but with the victims of the amia attack. ♦

Fuente: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/07/20/death-of-a-prosecutor